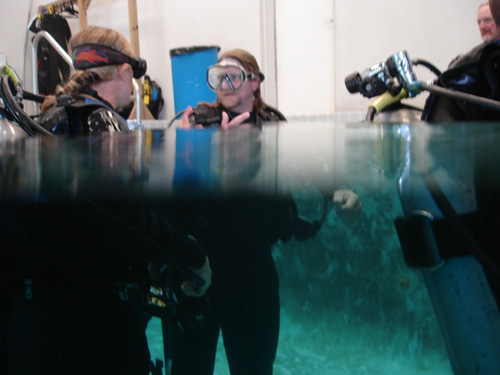

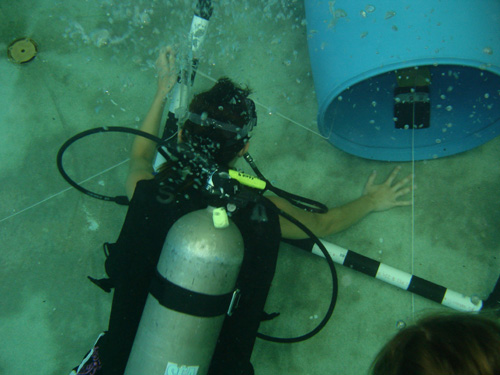

Honora Sullivan-Chin, a student in the 2009 LAMP Field School, undergoes black-out mask zero visibility training under the supervision of Graduate Student Supervisor Kendra Kennedy. The first two days of Field School are an intensive training session to prepare them for the challenges on diving in zero- and low-visibility conditions on the wreck of an unknown sailing vessel offshore which might be the lost privateer and former slave ship Jefferson Davis.

The recruiting announcements went out months ago. Those who signed up started filtering in last weekend–college students from all over the U.S.; from Florida, New York, Kansas, Minnesota, Chicago, and Connecticut. Our team of Graduate Student Supervisors–Kendra Kennedy and Bill Neal from University of West Florida, and Rachel Horlings from Syracuse University–had been prepping the Field House, shopping for groceries, and making scheduled student pick-ups at the Jacksonville Airport, under the coordination of LAMP archaeologist and conservator Christine Mavrick. Out on the water these divers and the remaining LAMP staff have been diving the site of an unknown ballast pile, laying in excavation trench gridlines and travel lines to aid with navigation in zero-visibility conditions. On shore we have been troubleshooting dredges, configuring equipment, and assembling a comprehensive course reader. The 2009 Field School is about to begin!

On Monday, all students and staff assemble at the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum for the first day of Field School. We meet in the Gallery for an orientation session. Chuck Meide, Director of LAMP, greets the students and introduces them to the facilities and operating procedures they will be using while working in St. Augustine.

Pictured from left to right, back row: Shelly Gray (U. Connecticut), Chris Borlas (U. Florida), Dr. Sam Turner (Director of Archaeology, LAMP). Front row: Megan Staley (U. Kansas), Honora Sullivan-Chin (Syracuse U.), Kaia Brown (U. Minnesota), and Wendy Drennon (Florida State U.). Not pictured are John “Tank” Brunswick, a LAMP volunteer and local nurse who is also taking the field school, and Samantha Shockly, whose trimester schedule at U. Chicago will prevent her from attending the first week of field school.

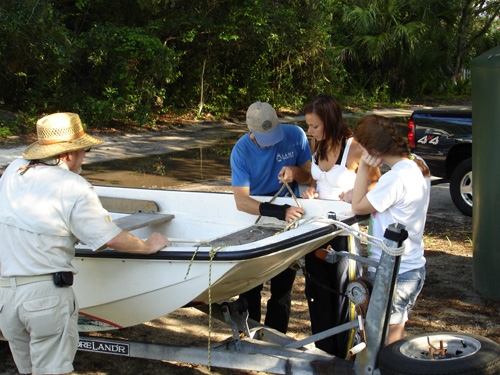

After a classroom orientation, which includes an overview of our Emergency Plan and Operations and Diving Plan, the students are broken up into groups, where they rotate through four stations to learn the basics of underwater mapping, compass navigation, knot tying, and remote sensing survey.

At the mapping station, Supervisor Rachel Horlings shows Chris and Shelly the basics of recording within a mapping grid or drawing frame.

Equipped with a folding rule and clipboard with waterproof paper, Chris and Shelly get busy recording the mock artifacts within this one meter by one meter unit.

The top of the Lighthouse gives a great view of this exercise. In addition to mapping with a grid, the students learn how to take offset measurements from a baseline. Both of these techniques will be used on the ballast pile site offshore.

At the knot-tying station, Dr. Sam Turner demonstrates how to tie off a line to a cleat while Tank, Kaia, and Wendy observe.

At the remote sensing station, Graduate Supervisor Kendra Kennedy teaches the basics of GPS navigation, side scan sonar, sub-bottom profiler, and magnetometer use to Honora and Megan.

After these exercises are complete, the students move to the local dive shop, Sea Hunt Scuba, for the swimming and snorkelling skills evaluation that is required by LAMP diving standards. Afterwards they get a lecture introducing them to the basic methods and theory of underwater and maritime archaeology by LAMP Director Chuck Meide. Then its on to the Field House to clean up and enjoy a barbecue with students and staff.

The following day we are back at the Sea Hunt Scuba pool for a scuba skills checkout. The students review all of the basic skills, such as mask-clearing, regulator recovery, buddy breathing, octopus breathing, BC ditch and don, and a controlled emergency ascent. In addition they master some of the more difficult skills including buddy breathing without a mask and the full rescue of an unconscious diver, including towing and rescue breaths at the surface.

But by far the most challenging drill is the black-out mask obstacle course. Visibility on the shipwreck site is often very limited, but with the torrential amount of rain that northeast Florida experienced in May and early June our site has been covered with a massive amount of mud flushed into the sea from our extensive inland waterways. Visibility has been total zero on the bottom. Some days the vis gets better a few feet up from the bottom, but some days the diver has to ascend 10 feet just to read his or her air gauge. Working dives in these conditions are challenging, but can be mastered with the proper training.

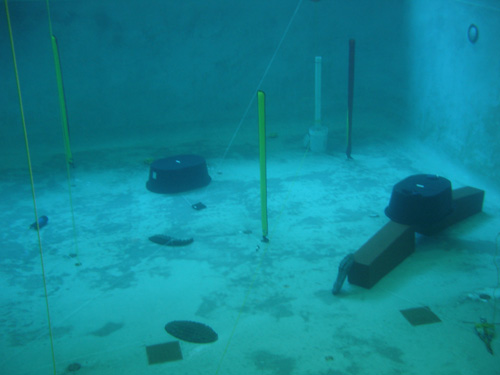

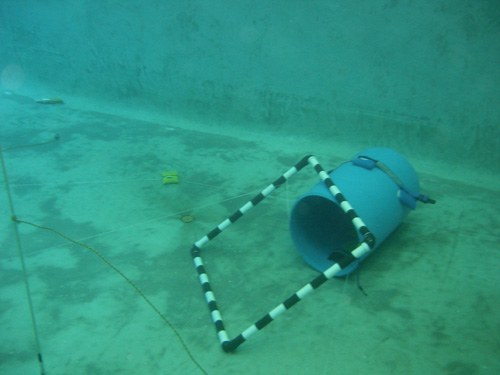

Because of this we have taken the time to set up a very challenging underwater obstacle course. While the students were at lunch, Chuck laid out a continuous zig-zagging line from a cave diver’s reel throughout the entire bottom of the pool. At some points this line ascends up to a ladder and back to the pool bottom, and up to the shallow end and back to the deep end. Then all manner of objects are laid along the cave line: barrels, large mock ship timbers made of fiberglass, rubber vats, PVC grids, floats rising up off the bottom, numerous bungee cords, and lots of loose and tight line. One long polypro line crosses the entire pool bottom, creating an entaglement hazard that cuts across most segments of the guideline. Here is one segment of the course where the guideline goes through a grid square and into and then out of a large plastic barrel. This arrangement proved to be one of the more challenging aspects of the obstacle course.

Two students run the course at the same time. Each starts out with their masks completely covered in duct tape at a floating buoy on the surface, and without the ability to see they make a descent to the bottom where the guideline is tied off. Their goal is to run the entire course, disentangling themselves whenever necessary, and reach the end of the guideline where they ascend a second buoy. At some point the two divers will run into and grope their way past each other.

Because of the numerous entanglement hazards that have been purposely placed in their path, each diver has a “guardian angel” staff diver who accompanies them closely during the course. They keep an eye on the blind divers but offer no assistance without a pre-arranged “I’m hopelessly stuck” hand signal. In addition to these two tenders, several other staff divers are in the water to constantly re-set the guidelines and other objects as they get dragged or moved around by the blind divers. Their other goal is to purposely entangle the blind divers by hooking bungee cords to their equipment throughout the dive.

Here, a bungee cord anchored to the bottom has been attached to Honora’s BC as she swam by. She’s not going anywhere until she realizes she’s caught and resolves the problem.

It doesn’t take her long to do so. After realizing she is caught in something, she follows the standard scuba diver’s plan of action–stop, breathe, think, act–and removes the offending entanglement.

Chris has been taught to swim with one hand on the guideline and one hand in front of his head so as not to run into any objects that might cause injury in an underwater no-vis scenario.

Here his guideline enters a space that his body cannot fit into. He feels around the object and eventually picks up the guideline as it comes out the other side, and continues with the course.

Kaia is following her guideline and runs into a tight polypro line stretched just a foot or so off the bottom.

But she feels it in time and avoids it by rotating her tank valve (a notorious entrangler) to one side and swimming under the line.

At times things can get pretty confusing down there, but all of our students are able to solve any problems they encounter with minimal confusion.

Here Megan takes off her entire BC, tank, and regulator kit because her tank valve was hopelessly entangled. After removing the entanglement, she puts her gear back on and continues in the right direction.

LAMP archaeologist and archaeological conservator Christine Mavrick giving hand signals that only some can see.

At the end of the day, our students feel like they have been run through the gauntlet and come out better divers at the other end. After one more evening lecture and briefing, Archaeology Boot Camp (Fin Camp?) is over. Tomorrow we will be in the field, diving in low visibility for real, where the wrecks are made of iron and wood and stone and covered in sea urchins and stone crabs. The staff are pleased with our students–they have all demonstrated excellent diving skills, and kept their cool under pressure in a stressful situation. The students are confident and eager to get to the real thing. Stay tuned for the continuing story of the 2009 Field School and the search for the Jefferson Davis offshore . . .