This past Tuesday, December 9th, LAMP took a second look at a wreck in Crescent Lake. The lake, a tributary of the St. Johns river and about an hour and a half southwest of St. Augustine, and it’s eastern shore is reputed to be the resting place of the steamboat Alligator. Our work with this wreck began earlier this fall and began through an interesting series of events.

Dan Smith, a retired National Weather Service meteorologist living in Fort Worth, Texas has long collected antique post cards. Many of these post cards feature steamboats, many of which were used in Floridian waters during the late 19th century and into the early 20th. Of Florida’s waters, Dan is specifically interested in the Ocklawaha River and its vibrant steamboat traffic when Florida was just beginning to settle its interior. For the following history and knowledge I owe all credit to Mr. Smith and I encourage you to read his “Voyage of the Alligator: The Story of an Ocklawaha River Steamboat and Some of the History of the Hart Line” (see here for the link to the article)

Team LAMP high-tailing it to the wreck site.

A little less than a year ago Mr. Smith contacted the Florida Bureau of Archaeological Research to see if he may be permitted to investigate a wreck lying in 2-5 feet of water on the eastern shores of Crescent Lake. The state underwater archaeologist Dr. Roger Smith asked LAMP to visit the site, putting us in touch with Dan, and thus the relationship began. After a series of phone calls we finally scheduled a trip down to the lake on September 28th.

Dan Smith (in blue shirt) talking with LAMP’s Dr. Turner.

The Ocklawaha is one of Florida’s only rivers to flow from south to north, much like its outflow source, the St. Johns. Very narrow and overhung with trees the Ocklawaha has a mean controlling depth of about four to five feet which made navigation for larger steamboats a touchy issue, especially during periods of low water. Steamer captains were constantly presented with challenges since the Ocklawaha isn’t known for its broad expanse and boats would blow a whistle when approaching a bend to let other boats know they were about to negotiate the pass. Two boats meeting at a bend couldn’t pass with safety and so one would have to wait for the other to make the turn. The tall nature of the boats also made them highly susceptible to careening outward while making a turn. One vessel, the Metamora of the Lucas Line, dipped her guard (a type of extended steamboat gunwhale) and took on sufficient water to sink her whilst navigating an oxbow. Folks familiar with the Ocklawaha often said the river was “more bends than miles”. Today, the river is a comparative backwater to the bustling days of the Hart and Lucas steam lines but nonetheless its history has maintained itself through sparse documentation. A few publications, mostly those of Dan Smith, have pieced together records from the area. Most notably, a book entitled “Ocklawaha River Steamboats,” by Edward Mueller provides us with a rich photographic history of the river’s steamers. This, combined with Mr. Smith’s research is the backbone of our knowledge on the riverine heritage along the Ocklawaha and to both researchers, we are grateful.

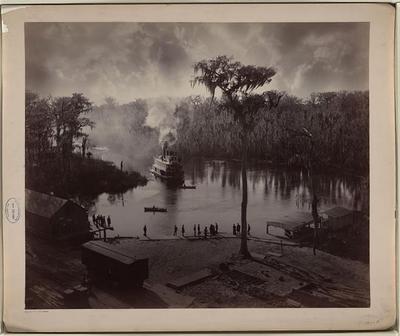

The landing at Silver Springs during the late 19th century. What boat is this coming in?

Silver Springs, a popular tourist attraction for snowbird Yankees as well as locals, was one of the main attractions on the Ocklawaha and to get there required passage aboard a steamer. Palatka was the main port of departure for Ocklawaha boats and scads of folks escaping the frosty New England winters journeyed up the river to take in the springs. Some of the most famous passengers on the Ocklawaha were Mary Todd Lincoln, Thomas Edison, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Ulysses Grant. Two major steamer lines ran out of Palatka, the Hart Line and the Lucas Line. In 1888 the little Alligator was laid down in Norwalk, a community on the St. Johns and was commissioned by a Cpt. C. W. Howard. Beginning life as a 57’ vessel with an 18’ beam and 3.5’ draft, she would have been one of the more diminutive steamboats in the area. Other contemporary vessels such as the Tuskawilla, the Metamora, and the Okeehumpkee were much larger and better appointed for passenger trade. While the Alligator didn’t serve solely on the Ocklawaha and saw service on the St. Johns, it appears that she was never a serious threat to some of the more established steamer lines.

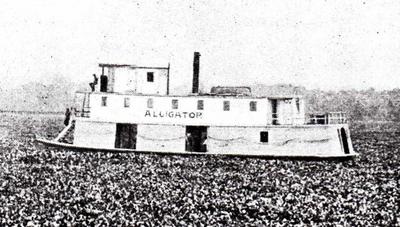

One of the earlier photos of the Alligator. This is how she looked during Moore’s tenure.

Only a year after she was launched the Alligator found herself back on the hard and went through a major refit. We do know from primary documentation that the initial construction of the Alligator used parts from several other steamers and, like many other steamers in the area, was considered more “assembled than built.” However, in 1889 she was lengthened to a total of 71’ and her propulsion gear was switched from a screw protected by two skegs to an inboard paddlewheel. Observers to the original build had noted that the screw design would “go alright until it hits a log.” Who knows whether the Alligator had, in fact, succumbed to this flaw but nonetheless she only lasted a year under original configuration. Sternwheelers on Florida’s rivers had to combat one common peril, water hyacinth. Eichhornia crassipes, an invasive species from South America we now know of as water hyacinth, had choked many of Florida’s inland waterways. Campaigns were underway during the last decades of the 19th century to eradicate the weed and poisons were liberally dumped into the Ocklawaha River and others to rid the scourge. Like kudzu, water hyacinth continued to thrive and boat designers had to engineer around it rather than rely on clear channels. The inboard paddlewheel seemed to be the best solution. Floating hyacinth ‘rafts’ would be parted by the bows and the completely enclosed paddlewheel would be less likely to get wound up in a mass of weed.

With this design change, and others, we begin to compile a list of attributes that any target resembling the Alligator must demonstrate to prove itself a reliable candidate. Dan’s research, however, uncovers much more about the Alligator including the further lengthening of the vessel, multiple deck and cabin changes, the relocation of the wheelhouse to something akin to a ‘Texas’ deck. When the Alligator burned in November of 1909 due to a fire of unknown causes, she settled into the bottom of eastern Crescent Lake as a vessel of 81’ with a twenty-one year career behind her. Five of these years, between 1891 and 1895, the Alligator was rented from its second owner, J. E. Lucas, and put into duty as Florida’s first research vessel. A Philadephia printing magnate’s son, Clarence B. Moore had a fascination with Indian mounds in the southeast. Apparently he done a fair amount of reconnaisance in the area, at least enough to warrant renting a steamboat during the winters and converting it into his private research vessel. Modifications were made to the interior spaces to include a dark room, storage for his excavation tools, and areas to work with the artifacts recovered from the shell mounds he was digging into. These early days of Floridian archaeology give the modern archaeologist reason to swell with pride as well as cringe. The methodology of Moore’s era were primitive compared to today’s but we need not harp on spilt milk long here since later decades saw the complete removal of burial and ceremonial mounds to the crushed shell matrix for roadbuilding. What Moore accomplished, in essence, was the salvage of many of Florida’s most unique cultural features before they would be lost to development. The little Alligator, however, was not in Moore’s designs for too long since after his work on the Ocklawaha he commissioned the building of a larger steamboat, called the Gopher, for work on the Aucilla River and elsewhere. Returning to service under a bevy of owners the Alligator again plied the waters of the St. Johns and finally back to the headwaters of the Ocklawaha. Between 1904-1905 Alligator was written off as ‘abandoned’ by her temporary owner Peter Cone. Cone sold out to two men named Dozier and Gibson who put her into service out of Leesburg on the Ocklawaha. It was during this service that she struck a snag and sank in 1906. However, the resilient boat wasn’t done-in here. She was raised, repaired and put back into duty. This late in her life she was in her last configuration and the wheelhouse had been moved down to the upper deck and integrated into a covered promenade.

Working on the site.

When the Alligator slowly came to grief in the fall of 1909 she did so somewhere on the eastern shore of what the wreck documents call “Cross Cut Lake”. After an exhaustive search of northeast Florida waterways, Mr. Smith has concluded that no known water feature is or has even been known as Cross Cut Lake. Since the paperwork may well have been filled out by a person wholly unfamiliar with Floridian waters Crescent Lake may have been chopped into a pseudonym for us to decipher. At any rate, the best candidate for the Alligator’s resting place is located in Grimsley Cove on the eastern shore of Crescent Lake. The real estate boom of the early 20th century gave reason for Alligator to cruise Crescent Lake likely hauling boxes of oranges as well as people across the lake from Crescent City. Crescent Lake is easily accessed from the St. Johns river via a slough known as Dunn’s Creek and was serviced by steamboats taking real estate investors to their newly purchased patches of swamp. By this time steamboat service was rapidly being overtaken by the railroad and steamers plied the St. Johns and Ocklawaha for only a few more years. Smith and other researchers have noted that the bones of some of the steam boats lay wrecked in Palatka well into the 20th century.

The wreck site.

When LAMP visited the wreck site in late September, the goal was to learn as much about the site as possible. Firstly, we are wary of referring to the wreck as the Alligator and considering the hunt ‘over’ until conclusive evidence can pin down the vessel’s identity. The water level in the lake was very high in late September and we were wading around up to our shoulders at times. We could definitely feel timbers in the hard packed sand and see the uppermost portion of the boiler sticking out of the water. Two other large metal cylinders lay on the bottom just next to the boiler, likely water storage tanks or condensers for the exhausted steam. One of the more exposed tanks seems like it was originally built as a pressure vessel given its heavy duty nature and through-stays (iron rods on the inside of the tank installed to prevent the ends from blowing out under load) but I suspect it was a reused tank from another vessel or factory used to hold freshwater for non-machinery use.

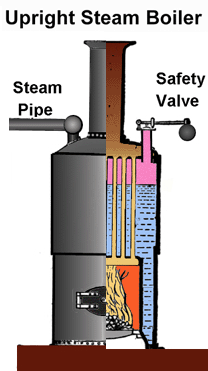

A boiler similar to that of the one we’ve been working with in Crescent Lake.

Looking into the boiler. The small tubes and round holes you see were part of the flue system, used to convey hot gasses from the fire through the water jacket, transferring heat to the water along the way.

The boiler is the most prominent feature of the wreck. It is approximately 4.2’ in diameter and 7.5’ in length. The style of boiler appears to differ from what we know about some other Ocklawaha steamers. Tuskawilla and Metamora both had locomotive style boilers. These boilers would have been a horizontal boiler and were adept at keeping weight low in the vessel, especially the Ocklawaha boats with their multiple decks and narrow beam. However, notes that Dan Smith has discovered point to the fact that Alligator received her boiler (likely only one) from another vessel, probably when her engine was fitted in Palatka and the boiler came from a steam launch. The boiler we are dealing with is an upright boiler and, while it plausibly came from a launch, it would have been a very big launch. Upright boilers were commonly used throughout the latter half of the 19th century and well into the 20th. Many are still in use today in older buildings as hot water heaters. Thankfully, the boiler we have on site is lying ‘butter side up’, if you will, and it allows us a good view of the more diagnostic aspects of the apparatus. When a fireman or engineer stands in front of an operational boiler he needs all of the control features to be readily at hand. This means that the firebox door (where fuel goes in), damper (to control airflow through the fire), injector (to put more water in the boiler), sight glass (to see how much water is in the boiler), and steam outlets (to get steam to the engine and other steam-requiring devices such as the whistle, water feed pump, dynamo, etc.) are all easily accessible. We were able to ascertain from examination that this boiler appeared to have only one system of checking the water level which is usally used as a backup system on more modern boilers. Three holes are drilled through the boiler wall and each one has a trycock screwed into it. This is simply a small valve that allows the fireman to open them quickly and see where the water level is inside the boiler. If steam comes out of all three holes then he knows that his water level is getting dangerously low. Most boilers of the era would have had trycocks but the primary system of checking water level would have been a sight glass, simply a glass column open to the atmosphere of the boiler and the level of the water could be readily observed much like a big coffee pot.

Jessica Clark (left), of First Coast News, talking with LAMP’s Christine Mavrick.

Around the boiler and its associated tanks is a complex scatter of heavy timbers. Trying to plot these out is no easy task and we will be returning to the site with a total station (what you see on the side of the road being used by surveyors.) Our main approach was to establish a grid over the site based on square meters. At each meter intersect we took a probe reading (plunging an iron rod into the sand to see if it struck hull or wreck materials) as well as a magnetometer reading. The magnetometer is reading the earth’s magnetic field as well as any distortion caused by ferrous objects in close proximity. Thus, if iron fasteners or artifacts from the wreck were buried we could theoretically find them. These readings will be loaded into a computer program that plots them out to create a map somewhat resembling a topographical map. Deviations in the magnetic background caused by iron concentrations will show up as highs or lows in the field and when we overlay this onto our created grid we can go back and identify where they reside.

Taking magnetometer readings. Author is on mag duty, LAMP Director Chuck Meide is recording.

Right now we are in the middle of the survey and will be returning to the site after the New Year to finish recording the grid and taking readings. The site, while no means a conclusive Alligator, holds much promise and we all look forward to further researching the site. We really can’t thank Dan Smith enough for his research and tenacity to hunt down one of Florida’s unique historic vessels.

The Alligator late in life.

Tank (LAMP volunteer John Brunswick) helping set the site baseline.

Returning to dock after the day’s work.